This article originally appeared in the February 2007 issue of Architectural Digest.

Very rarely are architects and designers asked to combine two adjacent ramshackle early-20th-century buildings into one sleek 21st-century residence, but that was the felicitous commission that architects Shirley Chang and B. Christopher Bene, of the Hong Kong-based firm Chang Bene Design, received from a Chinese businessman.

The larger of the two-story stucco buildings in the leafy former French Concession district of Shanghai had been a modest three-bedroom residence. Its wood floors and doors, plaster ceilings, small windows and steep staircase appeared to be suffering from terminal fatigue. A store had occupied the first floor of the neighboring building; a spiral staircase had once led up to a loft.

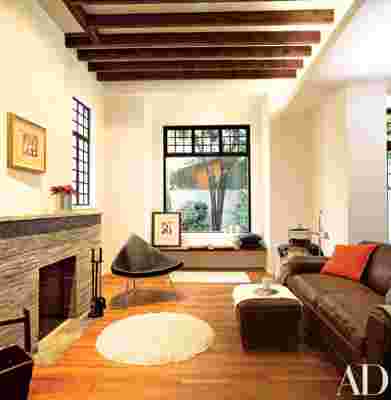

The challenges were many. The smaller building, for example, was two feet lower than the house next door; its floor would have to be removed and raised. Interesting opportunities presented themselves, however: A six-foot-wide gap between the buildings could be used to connect the two, and after a significant amount of both razing and raising, the combined new residence has a larger and more elegant entrance hall and a dazzling stair tower that joins the new and old structures horizontally and vertically.

"The real architectural intervention was the stair tower," says Chang, who was in charge of the renovation. "We weren't interested in doing historical preservation work here. We wanted to build a modern house for today." The new black-granite steps are wider than the original ones and have lower risers, making them at once more aesthetically pleasing and easier to climb. A white-lacquered rail is set against a backdrop of gray brick. "Many buildings in Shanghai were built with gray brick, and we found a good amount of it when we tore down the walls of the old house," Chang explains. "I thought the bricks were beautiful, so I used them on the wall in the stair tower." She had them laid on their sides. With the thin side exposed, they were stable and required a minimum of grout, and she favored the dry-laid look.

On the hall's terrazzo floor, which is composed of small pieces of white marble laid in pale green cement, is a solitary red Verner Panton chair she selected for its color and style: It is a bolt of color and makes the graphic statement Chang wanted for a staircase she describes as "a piece of functional sculpture."

The gap between the two buildings had been covered with a corrugated-fiberglass roof, which the architects had removed and replaced with a 90-degree skylight, or lantern, with one vertical plane of glass and one horizontal one. "Shanghai's weather from November to April is gray and drizzly," says Chang. "The lantern lets in welcome light. When I first saw the house, I took inventory of its assets, and one of them was a plane tree. Until we installed the lantern, you couldn't see the tree. Now it's visible and forms a green canopy, shading the stair-well during Shanghai's hot summers."

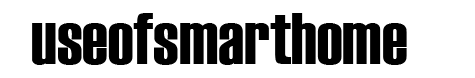

The entrance hall leads to a simple living/dining room with a new walnut floor. ("We chose it because it is less traditional and less yellow in color than the wood normally used in Shanghai," says Bene.) When Chang and Bene removed the plaster ceiling, they discovered original wood beams, which they left exposed. A new window seat overlooks the garden. Simple furnishings decorate the space, including an iconic George Nelson Coconut chair, which faces a leather sofa. Near it are a stripped-pine dining table and a set of upholstered chairs. New doors open onto a garden. The small kitchen was demolished and replaced with a state-of-the-art kitchen and a breakfast room that extend into the former shop.

Chang and Bene then reconfigured the second floor. In the master bedroom, they opened up the ceiling to create a double-height space out of a previously unused attic. A staircase goes up to a loft study and a roof terrace. The sunken tub in the master bath, formerly part of a bedroom, is topped with a domed skylight.

"The house is really about intimate spaces—vignettes, not panoramas," Chang says. "We tried to provide the occupants with glimpses of trees and sky and a slit of sunlight here and there as they move through the house, and that's what we captured in this project."