This article originally appeared in the April 2013 issue of Architectural Digest.

Exercise can have unintended benefits. One morning a few years ago, as I set out for a run in Central Park, a doorman at the prewar building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side where my partner, architectural designer Len Morgan, and I live whispered, “Penthouse on the market.” Our antiques gallery, Cove Landing , was down the street (we’ve since shifted to dealing privately and selling online), and we hadn’t been looking to move. But we were curious—tentatively, at least. This was the same penthouse whose radiators only a year before had sprung an insidious leak and caused our bathroom ceiling to collapse.

We immediately called to see the one-bedroom space, and it was worse than expected: ramshackle, crumbling windows, encrusted walls, and just a single door accessing a wraparound terrace with pink tile paving that resembled a slab of mortadella. It was also smaller than our apartment a floor below, but we could see the potential, especially in the vast terrace, which looks directly onto the soaring copper-clad dome of St. Jean Baptiste Church—a glimpse of Rome at our fingertips. As Len noted, “We were not so much buying an apartment but rather the right to rebuild the aerie on top.”

And so we did. Len handled all of the architecture, completely reconstructing every wall and customizing every surface. Most dramatically, he dismantled the exterior walls and inserted a series of nine pairs of steel-framed glass doors that reveal the sweeping skyline and bring a metropolitan immediacy into the apartment. He recast the bath as a compact dressing room, with a newly uncovered skylight, and made the former bedroom closet the bath, replacing a solid wall with a glass door that now separates indoor and outdoor showers on either side. We were able to reroute pipes and raise the ceilings 18 inches throughout, recapturing the old ventilation space made unnecessary by the addition of central air-conditioning.

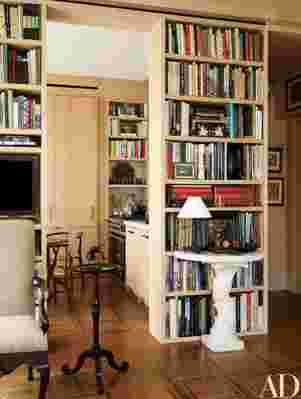

Len’s credo is a rigorous balance of volume, proportion, and scale. By relocating the openings between rooms, circulation was enhanced. A reclaimed 19th-century parquet floor unified the whole and introduced a sense of order and geometry, reinforced by the white-painted wood beams installed in the living room. A limited palette of limed-and-waxed-oak walls and white marble slabs provided a complementary air of restraint, as well as a self-effacing backdrop for the varied mix of antiques and rare finds we collect.

We’ve owned most of our things for years, and from the outset Len tailored the spaces specifically to those pieces. As a decorative arts dealer, it has long been my philosophy to buy furniture that feels honest and has good structural bones. A warm patina, the mellow figuring of richly grained wood, or a quirky design motif pleases me. I never seek “the perfect match” in a room and prefer to shuffle the deck to achieve a balance, a layering of the whole. My taste runs to unconventional objects, such as the living room’s cast-glass log sculpture by Rob Wynne and crumpled-bronze table by Silas Seandel. These are grouped with more traditional items, such as the mid-18th-century Irish mahogany elbow chairs covered in burlap that anchor the room with integrity and the nearby pair of 1930s Serge Roche white plaster consoles, featuring bases in the form of twisting tree trunks.