This article originally appeared in the February 2007 issue of Architectural Digest.

In a city as old and layered as NewYork is gradually becoming, early residential buildings often contain revealing pockets of social history. In just about any substantial apartment that went up in Manhattan before the Second World War and has not been dramatically altered since, you can find the incarnation of a way of life that nowadays feels as remote as black-and-white movies and women who don't consider themselves dressed unless they're wearing a pair of gloves. Servants' quarters and butlers' pantries, children's rooms tucked at the remote end of a long gloomy hall, a dining room definitively separated from a drawing room, a kitchen sequestered behind a swinging door—these component parts of the classic prewar apartment were designed for families where parents and children often lived separately, entertained differently and were waited on from dawn to dusk.

"There's a lot of romance to these old places," says interior designer Sandra Nunnerley, "but very little relevance to the way people live today." These were just about her first thoughts when she toured a handsome Park Avenue apartment that had recently been acquired by a young family. Arthur S. "Woody" Pier, the architect the clients had engaged, had a similar impression. "The clients were drawn to the apartment's grand scale, the solidity and quality of the construction, the location, its elegant lobby and well-trained staff," he recalls. But its old-fashioned layout, its poorly conceived kitchen, antiquated baths and awkward closets "did not come close to meeting the needs of the 21st century."

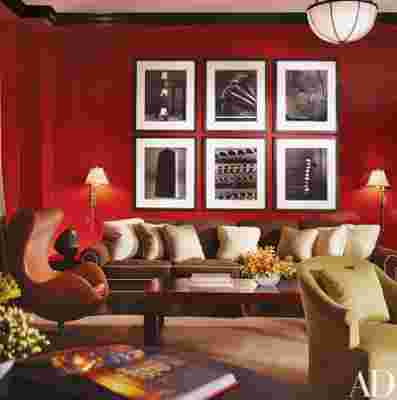

"I am just so tired of designing these living rooms that people walk by and peer into and say, Oh, isn't that a pretty room,' before they make themselves comfortable somewhere else," Nunnerley says. "People want to be close to their children these days, not separate from them. They entertain only on significant holidays. They don't have teams of servants. Woody and I made a proposal to the clients. We suggested they knock down the wall between the living and dining rooms and introduce a contemporary dimension to a period apartment."

The space became the multifunctional heart of the clients' new home. It is a living room. It is a library. There is a big round table where the couple's two children can do their homework. The parents can have a private dinner at this same table or host a large dinner by bringing up a large top that is stored downstairs. At the flick of various switches shades close, lights dim and a large screen drops down, and the room turns into a private theater. "Through design and architecture," Nunnerley explains, "the space can be experienced on many different levels."

Such transformations are often easier to dream up than they are to implement. "One of the most difficult challenges," says Pier, "is to create an interior that does not appear to be the result of a renovation. This can be particularly difficult when the audiovisual, electric, data and air-conditioning requirements are as demanding as they were here." Pier found inspiration in the vocabulary of British colonial architecture, whose articulated wood paneling and substantial cornices enabled him to finesse the installation of the room's mechanical systems (the husband has a passion for audiovisual equipment); Nunnerley, at her end, sought to imbue the reconstructed room with a sense of modernity, drama and plain fun.

"I wanted this to feel like a young apartment that was both practical and stylish," says the designer. Hence the lacquered walls, the ebonized bookshelves with their brass trim, the wall-to-wall carpet. Nunnerley deliberately left the room uncluttered so that there would be space for the children to play. And she mixed anchoring pieces of Modern classic upholstered furniture with zippier elements, such as an original Jacobsen Egg chair, a pair of reissued Mies Barcelona chairs and mid-century drip pottery lamps.

"Another thing I didn't want was to do a beige-on-beige color scheme. My clients weren't afraid of color, and that was a considerable help," says Nunnerley, who introduced pops of chartreuse in the combined living/dining room, used a yellow in the entrance hall and a deep inky green for the kitchen, because "it was at the back of the apartment anyway, and who says kitchens have to be all pristine and white?" In the master bedroom, by contrast, the designer streamlined the palette, using a gentle celery on the walls, an earthy oatmeal for the carpet and a chocolate brown for the headboard to create a space that is muffled and padded, a serene retreat for the busy parents of active young children.

So does the separation of the living quarters span generations after all? Responds Nunnerley with a laugh, "Not through architecture so much as the way you handle it. Mom and Dad might have a private cocoon, but the kids are only two steps away."