This article originally appeared in the April 2011 issue of Architectural Digest.

Having done everything from picking apples as a child on his family’s farm in Washington state to working summers in an Alaskan salmon cannery to pay his college tuition, the owner of a certain brownstone in Manhattan’s Upper East Side Historic District thinks of himself as hands-on. It’s a quality he shares with his wife, who grew up on a cattle ranch in Montana. Thirteen years ago they married and moved to New York City, where the husband had taken a job in investment banking.

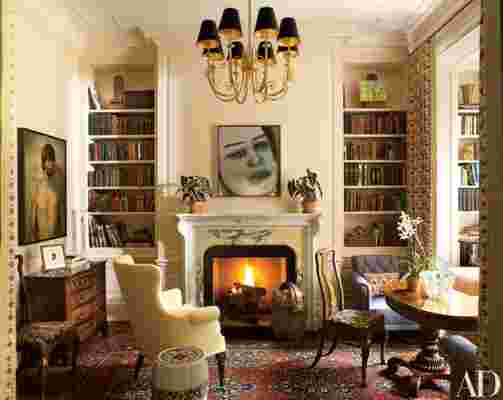

“We had always longed for a house in the city to take the edge off the city-ness,” the wife says, and yet a turnkey property held no appeal. “We’re big researchers, and we love doing projects together,” she adds. In 2005, after nearly a decade of apartment living—during which they had two daughters and began building a serious collection of art and antiques—they decided to take on a townhouse restoration. With their children asleep in the backseat of their car, the couple spent a series of weekend afternoons driving through every townhouse-rich quarter of the city until they found their quarry: a five-story Italianate brownstone built in 1874. Although it had been badly altered when the house was divided into four units after World War II, they assumed its bones were good. It was only after preliminary work that their architect, New Yorker Peter Pennoyer , discovered the deteriorated state of the structure and its interiors; there was, he says, “nothing of character to restore.”

But if their revival effort was now a full-fledged building project, they still felt it could be done in the spirit of an old house. And they seized the opportunity to redress the classic brownstone’s drawbacks, which included dark interior spaces and a distribution of rooms not suitable to the needs of a modern family. Pennoyer’s solution was to place the kitchen on the ground floor—at the core of the house—between a front family room, where the children love to play, and a dining room that overlooks a rear walled garden. The architect also removed a two-story 1970s-era addition that crowded the garden area and blocked light. He then created an entirely new back façade with expansive steel-framed windows.

As the project wrapped up, some three years after its start date, the wife felt the 7,500-square-foot house was lacking “warmth and comfort and approachability.” And she and her husband weren’t quite clear how best to integrate their carefully researched collections of antique carpets and 18th-century English, Irish, and Scottish furniture. Their fine art—including works by Picasso, Miró, and Matisse alongside those of Louise Bourgeois, Marlene Dumas, Alex Katz, Michaël Borremans, and Sigmar Polke—was of utmost importance.