The idea of having 3D TV is as old as TV and movies themselves. Since the start of cinema and TV broadcasts there have been ideas for how to make 3D work and how to instil the feeling that what you're watching is more than just a 2D medium.

Sadly, 3D has always been a bit of a fad. Remember the red/green glasses of the old days? Then the BBC doing that 3D Doctor Who meets Eastenders special for Children in Need? The problem has always been that it's a complete faff to get 3D to work. When HD screens came along, things started to look up. In this feature, we'll take a look at what modern 3DTVs do, how they do it and what type is best for you.

What is 3D TV and how is it made?

In many ways, the production of 3D is exactly what you might expect. One camera is used to make a 2D film, and two cameras are used to make a 3D film. The goal is to shoot distinct and very slightly separated images that can be used to feed your left and right eye slightly different views of the action. Doing this replicates the way we see 3D naturally.

To achieve this dual-shooting technique, a lot of movie and TV productions have a special rig for supporting two cameras. This has precise controls to allow the cameras to be set up for the correct offset to one another. This whole process is complex, but it requires that the cameras and optics are near-identical to each other to get the best results. There are also several video cameras that have forward-facing, dual-lenses. Panasonic and Sony both sell broadcast and domestic camcorders that can do this.

Of course, there are other ways to do 3D too. For example, it is something that can be post-produced, especially in movies where there's a lot of computer-generated action. As many films are now made against a green screen, there are some good opportunities to make what is sometimes called "faux 3D".

In all cases, a 3D film is made up of two distinct sets of frames: one for the left eye and one for the right eye. How you view these comes down to both the broadcast system and viewing system, which we'll look at now.

Active 3D

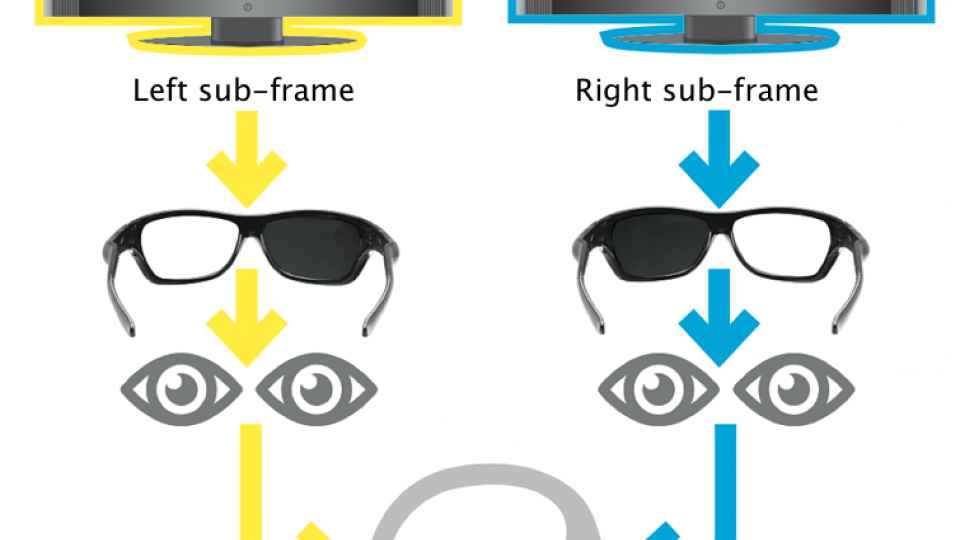

Active 3D works on plasma and LCD TVs and requires a set of powered glasses to make the 3D image. These are pretty light and comfortable these days, although some manufacturers still haven't got comfort quite right. Often the glasses will be rechargable too, with a USB socket to get power into them while they aren't being used.

These active glasses work by having lenses that have a liquid crystal layer applied to them. When voltage is applied to the lens, it turns almost completely opaque; without, they are almost completely clear. There is some light loss when you're looking through the lens even without a current applied, and it's this that can make the TV image seem a bit darker when you're watching with them on.

To produce a 3D picture, the TV displays the image for the left eye, then the image for the right eye. While it does this, the glasses shut out the light to the opposite eye. This happens 24, 25 or 30 times per second for each eye, so it is nearly impossible for you to tell it's happening, although some people do complain of flickering, and this might be why there are reports headaches with active 3D for a minority of users.

The big advantage of active 3D is that it gives you a proper, 1080p 3D image. This means that, at least in terms of picture quality, it's superior to passive 3D. There's a lot more to the situation than that though, and there are plenty of reasons to love passive 3D.

Passive 3D

The first thing that's great about passive 3D is that the glasses are dirt cheap. While active shutter glasses cost tens of pounds, passive glasses cost tens of pence, at the most.

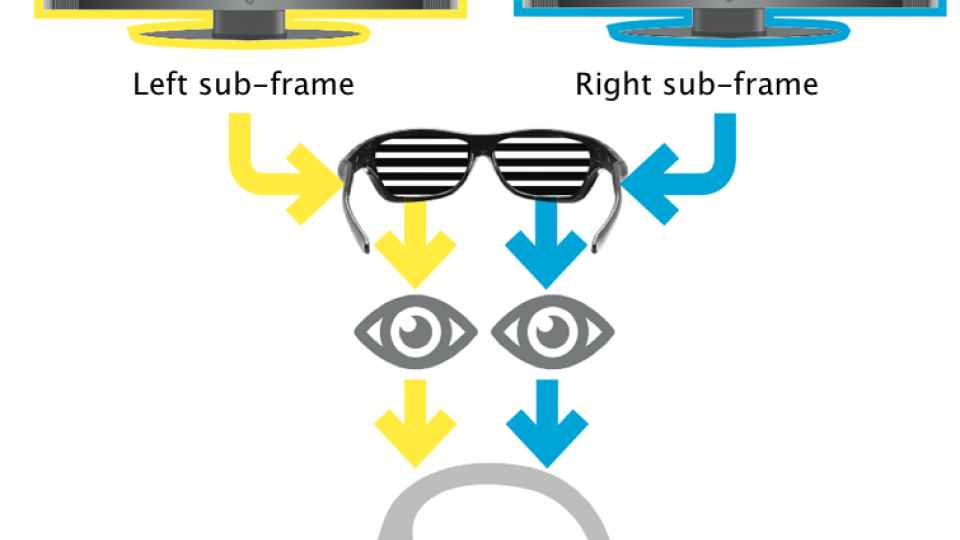

For home use though, the main downside of passive 3D is that it displays half the resolution of active 3D. This is because the images for both eyes must be on screen at the same time. In front of the LCD screen - there are no passive plasma sets - there is a filter, which polarises each line differently to the next. The TV then displays the two 3D images (left and right), at the same time: one image gets the even-numbered lines, one image gets the odd-numbered lines. This process is known as interlacing.

Each lens in a passive system is polarised to match a different set of lines. In that way, your eyes only see the image meant for them. The downside is that interlacing cuts down on resolution: with a passive 3DTV you'll see a 1,920 x 540 image with each eye.

That is, full horizontal resolution, but half the vertical. In practice, this is rarely a huge problem. Most people consider that passive 3D is much more comfortable to use for long periods, and if you have lots of people over to watch movies and sport, it's really the most practical and affordable system.

How is 3D broadcast on TV?

If you are a Sky or Virgin customer, you will have access to some 3D content. Most of it comes from Sky's dedicated 3D channel, which carries a mix of standard TV shows and pay-per-view events and movies.

For broadcast, capacity is always limited so sending a full-fat 3D signal is not an option. To get over this, broadcasters use a method called side-by-side. This takes the two images of 3D for left and right eye, and places them next to each other on the screen, so that they take up the same amount of space as a standard HD frame. When you look at it on a 2D TV, you see two near-identical images, which are squashed so everything appears tall and thin. Your 3D TV then takes these two images and presents them using whichever 3D technology is has built in.

The result is a 3D image that is technically HD, but it is considerably lower quality than a full HD 3D movie from a Blu-ray. The results are usually pretty good though, and Sky's 3D output is considered some of the best around. Technically, Sky could transmit full HD 3D, but it would require new set-top-boxes to work, and would use up a lot of bandwidth.

How does 3D Blu-ray work?

When it comes to Blu-ray, things get a lot better for 3D. You can have a full HD 3D image that gives 1080p pictures to the right hardware - passive 3DTVs can't display 3D in full HD, but active sets can (more on this later).

When 3D came along, a new compression system was developed that allowed huge space savings to be made, allowing the extra frames required for 3D to fit on a regular disc. This means both the left- and right-eye images are Full HD frames with none of the compression you get with broadcast 3D. It still takes more storage space, so on some films, it may affect the amount of extras on the disc, but that's hardly a problem as second discs are common on the HD format anyway. The two frames are then displayed according to the viewing technology in your TV.

Cinema vs home 3D

There are several competing formats in cinema 3D. The one you experience will depend on which cinema you go to. Mostly cinemas these days use some form of passive 3D, which means they don't need to provide expensive active shutter glasses. Early IMAX 3D used active glasses though, so it's not unheard of.

Dolby has a system that is passive in nature, but requires a slightly more expensive set of glasses. The advantage for cinemas, is that they don't need to replace their screen to use the Dolby system. Instead, the glasses filter colours based on their wavelength and a rotating filter on the front of the projector allows image to be directed to the correct eye.

For the most part though, the dominant 3D format for cinema is RealD, which uses a polarising filter and a set of cheap glasses. Images for the left and right eye are projected through a polariser attached to the front of the projector. RealD projects the images for left and right eye separately, one after the other and it does this 144 times per second and polarised glasses worn by the viewer mean each eye only gets the correct image.

Sony has a slight variant of this system, which uses a 4K projector to project the image for left and right eyes at the same time, giving each a 2K resolution for each image.

Glasses-free 3D

There is a goal in the world of televisions that one day we will have 3D that allows the viewer to wear no glasses, and still see the 3D effect. Technically, it is possible and TVs using the system have been demoed at CES and other trade shows for a number of years.

The biggest problem with glasses-free has been the quality. It's certainly possible to produce a 3D image, but it's not the sort of picture you could watch for any length of time. Additionally, you need to be sitting in the right place for the image to really have any depth to it, and when we've tried various prototypes, it has made us go a bit cross-eyed.

However, Dolby announced that it thinks proper, glasses-free 4K 3D TVs should start to appear in 2015. Dolby’s technology, which was developed with Philips relies on higher resolution displays being used to display 1080p 3D. In the demo at CES 2014, an 8K Sharp TV was used. Dolby says that its technology eliminates the problems usually found with glasses-free 3D, including the need to sit in a "sweet spot".

Headset-based 3D

One area that has massive potential is 3D displays that can be worn, like a pair of glasses or headset. Take Oculus Rift or Sony's Project Morpheus, which are both 3D headsets that can be used as virtual reality devices too.

Aside from the gaming potential here, because these devices have two screens that feed in to each of your eyes, they can produce an impressive 3D effect. They might be a bit weird to wear, and take some getting used to, but they certainly have amazing potential for a really vivid 3D experience.

Does 3DTV have a future?

Adding 3D to a TV is basically a very low-cost these days. For active 3D it adds nothing to the price beyond what the glasses cost. That means that TVs will almost all have 3D built in for many years to come. It has, however, never taken off as a way to sell TVs, much as the manufacturers wanted it to.

As long as Hollywood keeps making movies in 3D, then it's fair to assume 3D has a place in our homes. It seems like, despite not being a game-changer in the way Hollywood expected, there's enough demand in blockbuster movies for 3D production.

Perhaps one-day 3D will be replaced by something much better – holographic movies for instance. For now though, it looks set to be around for a while yet.